Get Care

- Request an Appointment

- Find Locations

- Find Doctors

- Programs and Services

- Clinical Trials

- Regional Care Center

- Contact Us

Ranked nationally in pediatric care.

Arkansas Children's provides right-sized care for your child. U.S. News & World Report has ranked Arkansas Children's in seven specialties for 2023-2024.

Manage Care

- Access MyChart

- Prepare for Your Visit

- Patient and Visitor Info

- Accommodations

- Insurance

- Online Bill Pay

- Medical Records

- Arkansas Children's App

It's easier than ever to sign up for MyChart.

Sign up online to quickly and easily manage your child's medical information and connect with us whenever you need.

For Healthcare Professionals

- Arkansas Children's Care Network

- Refer a Patient

- Healthy Planet

- Residency and Fellowship Programs

- Continuing Education

- Careers

- Research Institute

- Other Resources

Need to refer a patient?

We're focused on improving child health through exceptional patient care, groundbreaking research, continuing education, and outreach and prevention.

When it comes to your child, every emergency is a big deal.

Our ERs are staffed 24/7 with doctors, nurses and staff who know kids best – all trained to deliver right-sized care for your child in a safe environment.

Discover

Programs and ServicesPrograms and Services

View all specialties >

Expert care for your child.

Arkansas Children's provides right-sized care for your child. U.S. News & World Report has ranked Arkansas Children's in seven specialties for 2023-2024.

Family Resources

View all resources >- Arkansas Children's App

- Blog

- Patient Stories

- Better Today, Healthier Tomorrow Podcast

- Child Life and Education

- Family Support Services

- Social Work

- Resource Connect

Looking for resources for your family?

Find health tips, patient stories, and news you can use to champion children.

Health at Home

- Symptom Checker

- Community Engagement

- Natural Wonders

- Child Safety and Injury Prevention

- Better Today, Healthier Tomorrow Podcast

- The Center for Good Mourning

Support from the comfort of your home.

Our flu resources and education information help parents and families provide effective care at home.

About Arkansas Children's

- About Arkansas Children's

- Mission, Vision, and Values

- Our Leadership Team

- Awards and Recognition

- Angel One

- Patient Safety

- News

Children are at the center of everything we do.

We are dedicated to caring for children, allowing us to uniquely shape the landscape of pediatric care in Arkansas.

Research

- About ACRI

- Research Programs and Centers

- Our Researchers

- Clinical Trials

- Resources for Researchers

- Summer Science Program

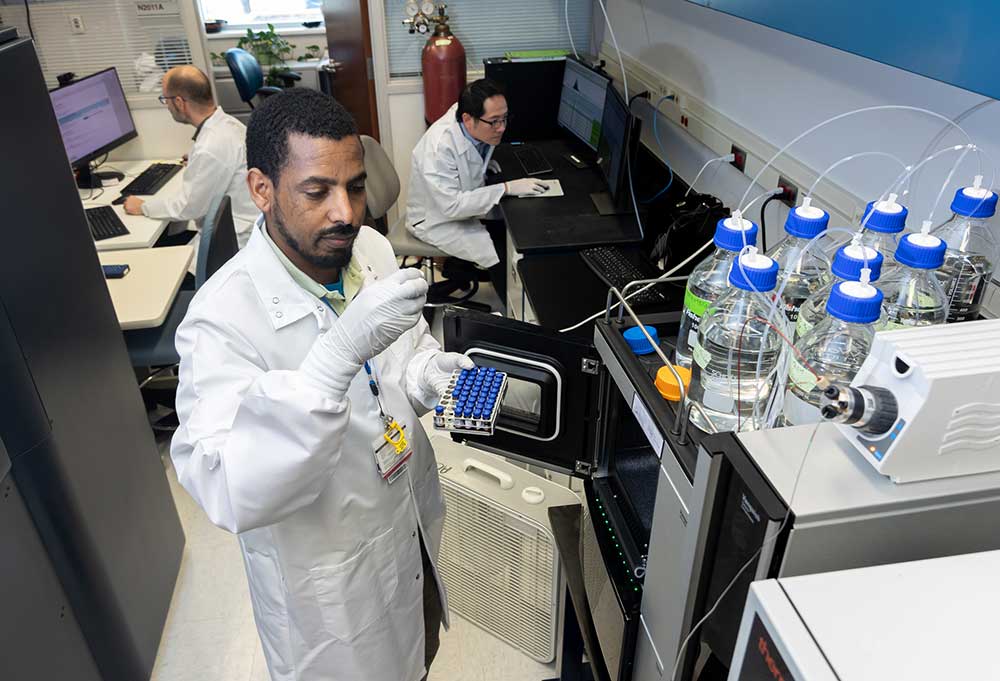

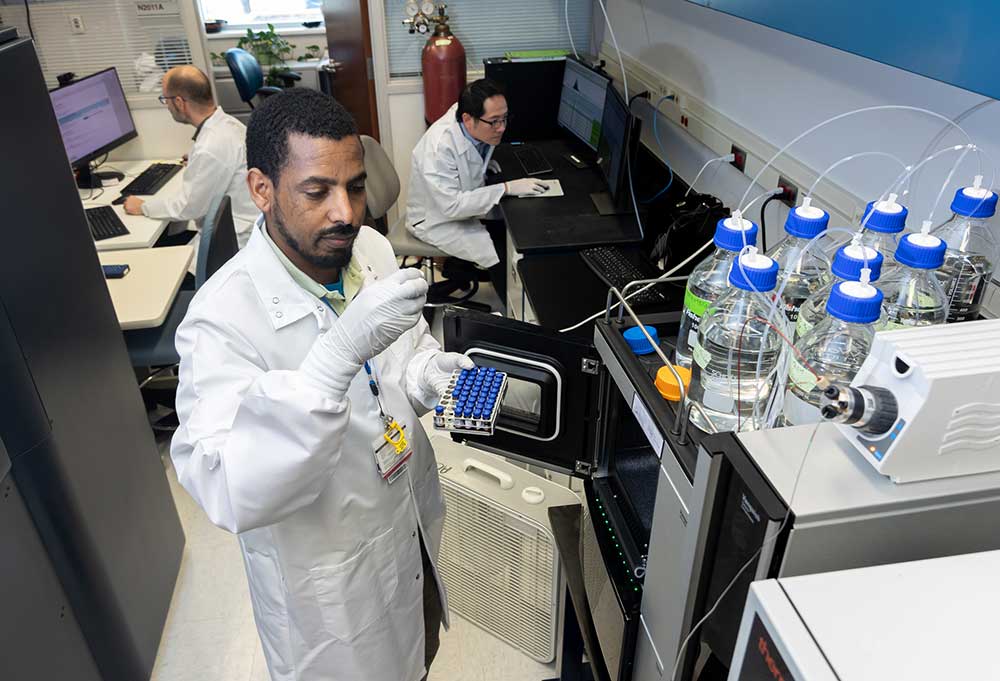

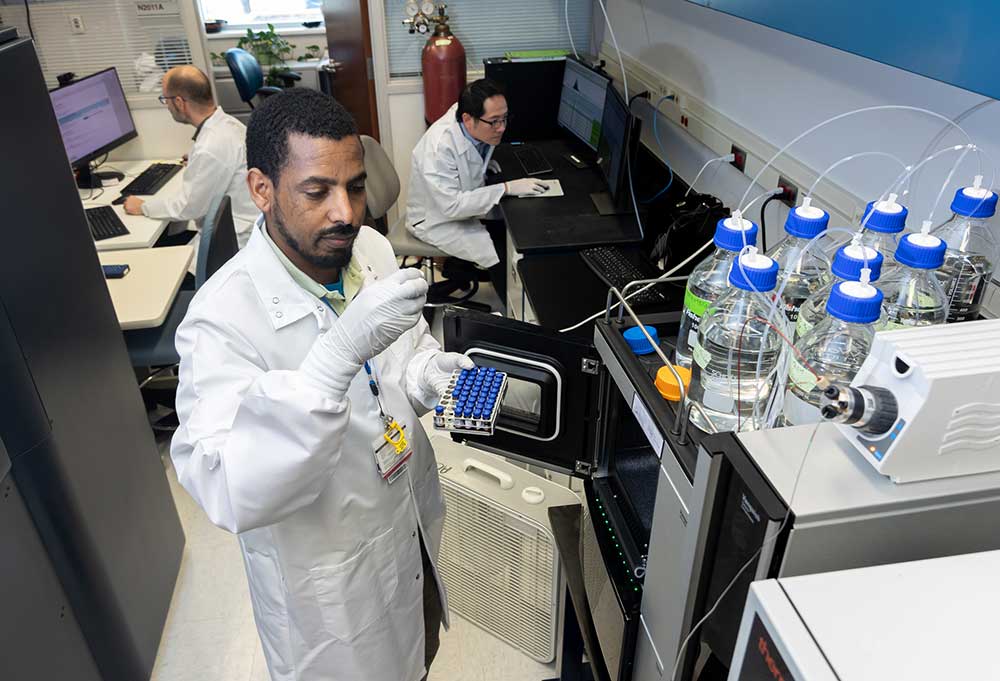

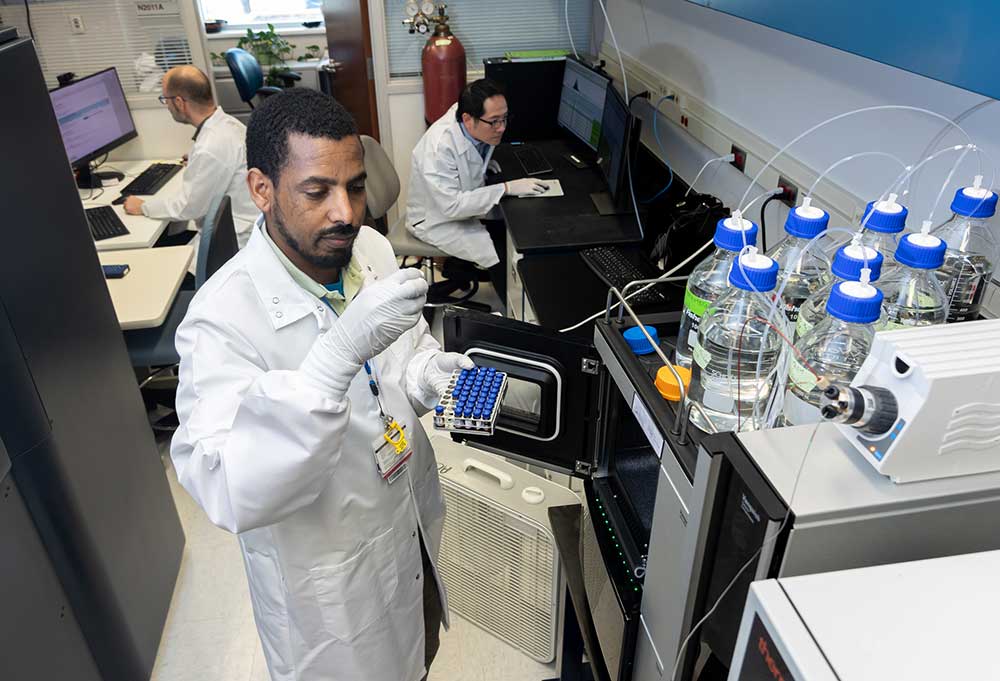

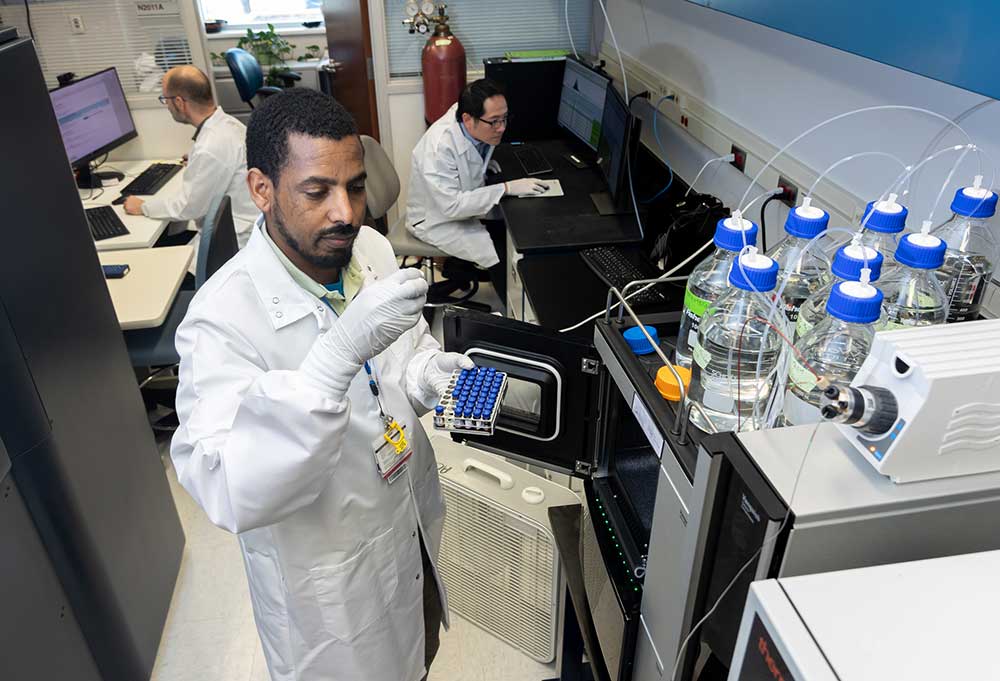

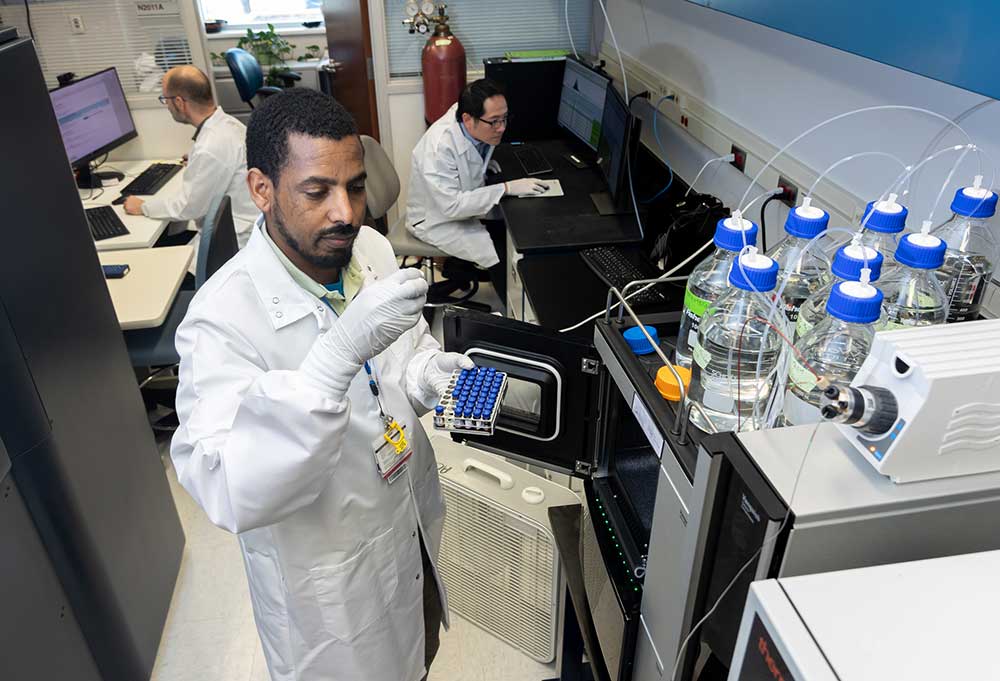

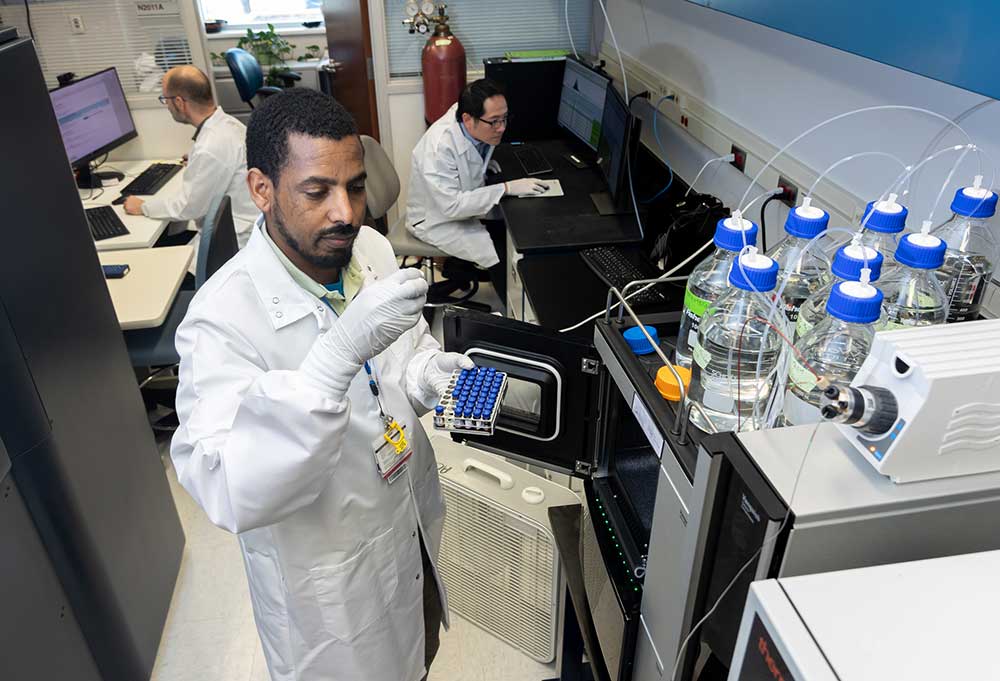

Transforming discovery to care.

Our researchers are driven by their limitless curiosity to discover new and better ways to make these children better today and healthier tomorrow.

For Healthcare Professionals

View all resources >- Arkansas Children's Care Network

- Refer a Patient

- Healthy Planet Link

- Nursing Resources

- Education and Training

- Research Institute

Need to refer a patient?

We're focused on improving child health through exceptional patient care, groundbreaking research, continuing education, and outreach and prevention.

Looking to make a difference?

Then we're looking for you! Work at a place where you can change lives...including your own.

Arkansas Children's Foundation

Every little bit matters.

When you give to Arkansas Children's, you help deliver on our promise of a better today and a healthier tomorrow for the children of Arkansas and beyond

Volunteer

- Ways to Volunteer

- Special Programs

- Volunteering in Little Rock

- Volunteering in Springdale

- Donate Toys and Gifts

Become a volunteer at Arkansas Children's.

The gift of time is one of the most precious gifts you can give. You can make a difference in the life of a sick child.

Join our Grassroots Organization

Support and participate in this advocacy effort on behalf of Arkansas’ youth and our organization.

We Transform Discovery to Care

Scientific discoveries lead us to new and better ways to care for childlren.

Research Centers

- Arkansas Children’s Nutrition Center (ACNC)

- Center for Childhood Obesity Prevention (CCOP)

- Center for Clinical Translational Pediatric Research (CTPR)

We Transform Discovery to Care

Scientific discoveries lead us to new and better ways to care for childlren.

We Transform Discovery to Care

Scientific discoveries lead us to new and better ways to care for childlren.

We Transform Discovery to Care

Scientific discoveries lead us to new and better ways to care for childlren.

Operational Resources

- Resources for Researchers

- Information Systems

- Institutional Information

- Pediatric Clinical Research Unit

- Using Controlled Substances in Research

We Transform Discovery to Care

Scientific discoveries lead us to new and better ways to care for childlren.

We Transform Discovery to Care

Scientific discoveries lead us to new and better ways to care for childlren.

Every little bit matters.

When you give to Arkansas Children’s, you help deliver on our promise of a better today and a healthier tomorrow for the children of Arkansas and beyond.

Programs & Events

More volunteer opportunities.

Your volunteer efforts are very important to Arkansas Children's. Consider additional ways to help our patients and families.

Ways to Volunteer

Ways to VolunteerWays to Volunteer

Join one of our volunteer groups.

There are many ways to get involved to champion children statewide.

Make a positive impact on children through philanthropy.

The generosity of our supporters allows Arkansas Children's to deliver on our promise of making children better today and a healthier tomorrow.

Learn more about your impact.

Read and watch heart-warming, inspirational stories from the patients of Arkansas Children’s.