Protect your family from respiratory illnesses. Schedule your immunization here >

Ranked nationally in pediatric care.

Arkansas Children's provides right-sized care for your child. U.S. News & World Report has ranked Arkansas Children's in seven specialties for 2025-2026.

It's easier than ever to sign up for MyChart.

Sign up online to quickly and easily manage your child's medical information and connect with us whenever you need.

We're focused on improving child health through exceptional patient care, groundbreaking research, continuing education, and outreach and prevention.

When it comes to your child, every emergency is a big deal.

Our ERs are staffed 24/7 with doctors, nurses and staff who know kids best – all trained to deliver right-sized care for your child in a safe environment.

Arkansas Children's provides right-sized care for your child. U.S. News & World Report has ranked Arkansas Children's in seven specialties for 2025-2026.

Looking for resources for your family?

Find health tips, patient stories, and news you can use to champion children.

Support from the comfort of your home.

Our flu resources and education information help parents and families provide effective care at home.

Children are at the center of everything we do.

We are dedicated to caring for children, allowing us to uniquely shape the landscape of pediatric care in Arkansas.

Transforming discovery to care.

Our researchers are driven by their limitless curiosity to discover new and better ways to make these children better today and healthier tomorrow.

We're focused on improving child health through exceptional patient care, groundbreaking research, continuing education, and outreach and prevention.

Then we're looking for you! Work at a place where you can change lives...including your own.

When you give to Arkansas Children's, you help deliver on our promise of a better today and a healthier tomorrow for the children of Arkansas and beyond

Become a volunteer at Arkansas Children's.

The gift of time is one of the most precious gifts you can give. You can make a difference in the life of a sick child.

Join our Grassroots Organization

Support and participate in this advocacy effort on behalf of Arkansas’ youth and our organization.

Learn How We Transform Discovery to Care

Scientific discoveries lead us to new and better ways to care for children.

Learn How We Transform Discovery to Care

Scientific discoveries lead us to new and better ways to care for children.

Learn How We Transform Discovery to Care

Scientific discoveries lead us to new and better ways to care for children.

Learn How We Transform Discovery to Care

Scientific discoveries lead us to new and better ways to care for children.

Learn How We Transform Discovery to Care

Scientific discoveries lead us to new and better ways to care for children.

Learn How We Transform Discovery to Care

Scientific discoveries lead us to new and better ways to care for children.

When you give to Arkansas Children’s, you help deliver on our promise of a better today and a healthier tomorrow for the children of Arkansas and beyond.

Your volunteer efforts are very important to Arkansas Children's. Consider additional ways to help our patients and families.

Join one of our volunteer groups.

There are many ways to get involved to champion children statewide.

Make a positive impact on children through philanthropy.

The generosity of our supporters allows Arkansas Children's to deliver on our promise of making children better today and a healthier tomorrow.

Read and watch heart-warming, inspirational stories from the patients of Arkansas Children’s.

Hello.

Arkansas Children's Hospital

General Information 501-364-1100

Arkansas Children's Northwest

General Information 479-725-6800

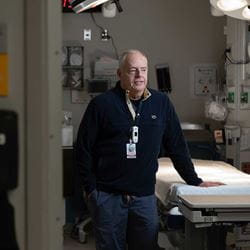

Scrubs and a Paint Brush: Arkansas Children’s Kendall Stanford Gives Gifts of Healing, Art

Published date: March 08, 2024

Arkansas Children’s celebrates team members for who they are. Some have fascinating stories to tell both inside and outside of their careers, whether it’s an interesting hobby, a unique experience, an inspiring back story or something they’ve done to change the world for the better. We are sharing these stories in our in-depth profile series, “Celebrating Who We Are.” In this article, we're exploring the life of Kendall Stanford, M.D., a pediatric emergency medical specialist and abstract artist.

There is never a plan when Stanford starts painting. It’s simply squeezing bright or metallic colors — yellows, silvers, greens, blues, reds — onto a large canvas, casually moving the brush as shapes appear.

There is never a plan when Stanford starts painting. It’s simply squeezing bright or metallic colors — yellows, silvers, greens, blues, reds — onto a large canvas, casually moving the brush as shapes appear. While many abstract artists let their emotions guide them, Stanford contends it’s “mindless,” once a way to decompress from the stressors of working in pediatric emergency medicine. Today, his motivation is the joy of giving out his work to make others smile.

Despite creating about 200 paintings over the past 25 years, he is adamant he’s not an artist.

“I can stay down there and paint for four or five hours, and I’m like, ‘Seriously, this isn’t art.’ It’s bright colors, and I know how to make certain things happen. But some people work on stuff for months; that’s not me,” he said with a laugh. “I struggle with selling stuff because I didn’t think they were that good. I know people were buying them, but I feel like a fraud. It’s easier for me to give them away. I just can’t take it that seriously.”

Medicine and art intersect in some ways for Stanford, a pediatric emergency medical specialist at ACH and a professor of pediatrics in the section of pediatric emergency medicine at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, who stumbled into each passion in an unlikely way.

“Maybe it’s sort of that same feeling — you give something, and there’s that immediate gratification, like helping someone,” Stanford said. “It’s always miraculous to make someone feel better.”

Texas to Oklahoma

Stanford, 64, was born the oldest of three children to the late Kenneth W. and Carolyn Stanford in the small town of Stamford, Texas. The closest he got to art was spending time in the summers with his grandmother, Nell Bennett, whose home smelled of turpentine from her oil paintings.“Both families were farmers, but my grandmother was an artist. She was famous in their little town. I told you I have stuff in 25 states; she had probably 35 families that had her Blue Bonnet paintings in Stamford, Texas. She sold it at art sales and stuff,” Stanford said. “My mom has a couple in her house. I have a painting of hers, sunflowers, that looks very much like van Gogh’s sunflowers.”

Her artistic messiness is mirrored in his workshop, now below his home instead of in his garage.

“I buy paintbrushes in bulk because I never wash a paintbrush,” Stanford said.

The family moved frequently in his first six years as his father served in the U.S. Army. They eventually settled in Amarillo, Texas. Stanford went to two years of junior college in Amarillo and then to West Texas State, now West Texas A&M University in Canyon, Texas.

Stanford was an accounting major, and neither art nor a medical career were on his radar. While in college, he worked with his contractor brother, running a remodeling business.

“We started working for three or four doctors; we redid their kitchens. The more time I hung around them, they said, ‘You should consider medicine.’ There was never anybody in my family that had done medicine,” Stanford said. “One of them got me a job in the surgery suite. I was a tech in the operating room. When I left junior college in my junior year, I went to university and became a science major.”

He graduated from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School in Dallas in 1986 and went to the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center in Oklahoma City for his pediatric residency and chief residency. While he initially didn’t have a thought to be in pediatric emergency medicine, it became his passion.

“I think it was my third or fourth day of chief residency when five of the nine ER faculty left and took a job in Fort Worth. So, they were desperate for help in the ER and asked me if I would work shifts,” he said. “When my chief year was up, they asked me if I wanted to stay on, and I stayed on.”

One of his most significant days while working in Oklahoma was April 19, 1995, the day of the Oklahoma City bombing, a domestic terrorist attack on the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building that killed 168 people. He was supposed to receive the Stanton L. Young Master Teacher Award that evening.

“A kid came in with a piece of brick sticking out of his forehead, and it looked fake,” like disaster drill make-up, he said.

They treated flying debris injuries on both adults and children.

“It’s just evil. We don’t live with that in the United States,” he said, adding that the city’s resilience stays with him. He has never visited the memorial site. “All those people we had been teaching across the city came together and helped our city heal. Even the new trainees were right there; they were side by side. It’s amazing how something so miraculous can come out of such tragedy.”

Painting for Others

While Stanford fell into the world of medicine, landing at Arkansas Children’s Hospital in October 1999 put him right where he was supposed to be.“I like pediatrics; being around pediatricians is fun. This is just a great place. The state’s beautiful, there are good people; there’s quality — quality medical students, quality residents, quality faculty. It’s corny, but it’s family,” Stanford said.

It was also 25 years ago that he happened to start his artistic endeavors, though he still scoffs at the notion. During a trip to New Mexico, his friends tried to purchase a roughly $7,000 abstract painting for their home, but it sold when they returned to Taos.

“I said, ‘Well, you know, I think that was just meant to happen because I know I could paint that in my garage,’” Stanford said.

A couple of weeks later, armed with some half-off art supplies, he recreated the abstract painting and dropped it off at his friends’ home, leaving it leaning against their back door.

“They called, and they were just kind of discombobulated. They said, ‘Did you buy us that painting?’ I said, ‘No, I painted that. I told you I could do it in my garage.’ So, they hung it in their house,” he said.

From there, a designer friend saw it and offered to sell some of his artwork if he continued painting.

“Anytime I would go home, I would just literally lean something up against the trash cans in the garage and try to paint something. Some of them were pretty decent, and some were pretty trashy. So, I would just paint over them and cover them up,” Stanford said. “I’m probably the best at kid’s paintings and bathroom paintings. Almost all of the pediatric residents and fellows, if they’ve had a kid during residency, I’ll paint something for them.”

Today, his art hangs everywhere, from an apartment in Germany to a multi-million-dollar beach house in Florida. He’s donated art to charities and organizations like Candlelighters of Central Arkansas, breast cancer awareness groups, Our House and Youth Home. For a live auction benefiting Youth Home, they requested his painting have an artist bio. Stanford explained that somebody had stolen his art from his hairdresser’s salon about four months prior, which had hosted an art show for his abstract paintings. Some of the paintings were found by the police at a local pawn shop, giving him the perfect fodder for a short bio.

“I put on this little blurb that I was a self-taught artist who was hanging internationally and had been stolen and recovered by the police,” Stanford laughed. “Anybody who didn’t know me probably thought I was a real jerk, but it was just so tongue in cheek.”

But his most meaningful work is hanging at several places throughout ACH and in the homes of his team members. For years, painting was a way to decompress after his five-minute drive home from an ED shift, but now, since his commute is longer and he moved his painting space, his art is more about making people smile.

“Now it’s mostly, ‘Oh, I need this for the residents, so I have to go down and paint something today,’ or someone asked me for one. I would really have to hate someone to tell them no if they asked me for a painting, and that just doesn’t happen,” he said.

Blessed at Arkansas Children's

Stanford admits he’s always been “creative,” but, for him, art is more task-oriented, similar to his work in the ED.The most typical cases Stanford said he sees in the ACH ED today are lacerations, respiratory illnesses, broken bones and complex medical cases. He approaches each case with compassion but also a decisive mindset, collaborating with his team to deliver the best care.

“When something’s going bad, you can’t break down. You got to buck up and go after it and be strong for the family and sometimes you have to tell the family they need to be strong for the other people in their family. You have to pick them up off the floor sometimes,” he said.

“When something’s going bad, you can’t break down. You got to buck up and go after it and be strong for the family and sometimes you have to tell the family they need to be strong for the other people in their family. You have to pick them up off the floor sometimes,” he said. Even though physicians must compartmentalize some of the more challenging days to continue doing their jobs at a top level, Stanford said he learned within his first years of practicing medicine in Oklahoma how important compassion is to prevent a hardened heart.

“I can tell you without question the worst day I ever had in medicine,” he said, recalling a time when they could not successfully resuscitate a pediatric patient. “I talked to the family, and then I walked out of the room. Someone was sitting there, and I started talking about what we were going to get for lunch. I thought, ‘Oh my God, who am I and what has happened that I could two minutes ago tell a family their kid was dead and now be worried about lunch?’ It was that over-compartmentalization that had happened. I just thought, ‘This is not who I want to be.’”

It was a turning point, a lesson he leans into during the more challenging moments of his life’s calling.

“I really struggle when a child dies, and they have like an 8-, 9- or 10-year-old sibling that’s in the room with them. They’ll either be rubbing their hand or hair,” he said. “I struggle when the dad is more emotional than the mom. And then the mom’s got the dad’s head on the shoulder; that gets me every time. I have to literally bite the inside of my lip.”

That compassionate nature has served him well at Arkansas Children's with patients and his staff.

With patients, he chooses to crouch beside their bed or sit on the floor and does not wear his lab coat to avoid being intimidating.

“I’m not there to tower over them. I’m there to help them,” Stanford said. “It’s why you put chairs facing each other instead of side by side. It’s why a round table is more fun to sit at than a banquet table.”

Even after several years in pediatric medicine, Stanford still gets excited by certain cases, whether it’s figuring out the correct diagnosis for a challenging illness or a simple, quick fix. One of his favorite procedures is fixing a radial head dislocation, when a child’s arm has been pulled and they cannot rotate it.

“The parents are crying because they think they broke their kid’s arm. You put it back in place and they’re immediately using their arm again,” he said. “As hard as I try to be a good educator, if I know that that’s what a kid has, I cannot help myself from fixing it.”

In much the same way, Stanford can’t help going above and beyond for his clinical team, bringing snacks for every shift he works, typically from 4 p.m. to midnight, and ensuring his medical residents are prepared to be the next generation of skilled caregivers. In 2022, Stanford was the Ruth Olive Beall Award winner, given annually to a physician who consistently displays the Arkansas Children’s values of safety, teamwork, compassion and excellence. In his nominations, his team described him as the “glue” and “heart and soul” of the ED.

“There’s a great team around you here. The nurses are excellent. The pharmacists are excellent. The respiratory therapists are excellent. We all stay trained. We all know our jobs, like when we have a trauma patient, teams are set up. When we have a sick kid come in, we have advanced life support teams. The nurses are all assigned to their duties, and they know what they’re supposed to do. The techs get in there. It all just happens bam, bam, bam, bam, bam,” he said. “It’s immediate. But it’s the team that’s immediate, not just an individual.”

Whether he’s saving a life or putting a smile on someone’s face with his art, it’s all part of giving thanks for the life he’s been given.

“I live a very blessed life. And part of that blessing is getting to be a part of this Arkansas Children’s team. It’s just a joy every single day,” Stanford said.

Are you interested in becoming an Arkansas Children's team member?

Click here to view our current job openings